Traum, 3D video-projection 7.41 min, sound: Ane Trolle, Porn actors: Danske Misse, Carlos

The word trauma stems from Greek and means wound, and traum (German) means dream

Risø

Simian, 2021

Text: Amalie Smith

Kirstine Aarkrog’s exhibition Risø brings together two spaces that might initially appear disparate: the Danish nuclear research facility Risø and a therapy room of the kind we see in psychoanalysis. In Aarkrog’s imagery these two spaces share a formal likeness, and the processes with which they are concerned correspond logically: radioactive material implants itself in the body and affects it from within, as does psychological trauma.

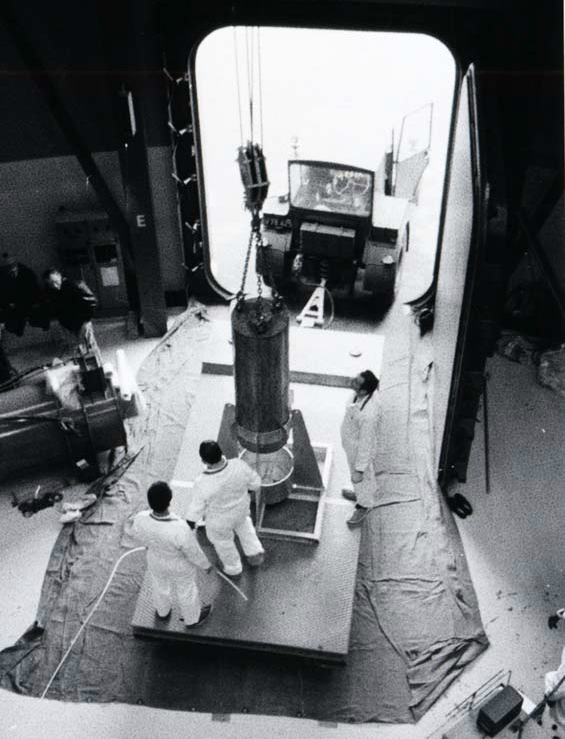

Risø nuclear research facility was inaugurated in 1958 on a peninsula in Roskilde Fjord, and throughout the following decades the centre served as a hub for research in the peaceful utilisation of nuclear energy. Three reactors were built, and enriched uranium was flown in from the US. Meanwhile, the Cold War unfolded in the form of an arms race in the East and West, and the superpowers’ nuclear bomb tests were detectable as radioactive fallout everywhere on the planet. Some of it landed on pastures and was consumed by cows that produced radioactive milk, and radioactivity could subsequently be measured in small concentrations in baby teeth.

Kirstine Aarkrog’s maternal grandfather, health physician Asker Aarkrog, worked at Risø from its founding until his retirement in 1999. Her grandmother was a psychiatrist. The nuclear family (a term that was introduced in the same period) lived in employee housing on site, and Kirstine’s mother’s baby teeth were used in radioactivity research.

The threat of a nuclear third world war loomed large. In such a war, the entire globe would be contaminated. People prepared in several ways – at Risø, among other things, by developing a method for purifying milk contaminated with radioactive material. The purification of milk was a balancing act: if purified too zealously, you risked losing the milk’s nutrients, thus rendering it ineffectual. A taped conversation between Kirstine Aarkrog and her grandfather about the purification of milk forms the basis for the exhibition.

Milk – this miracle drink which builds up children’s bones and, in doing so, maintains the body of society. In milk, the collective and individual are unified. What other invisible entities flow through families along with milk? Which traumas are passed down from generation to generation, and which decay over time? And if radioactivity could be eliminated from milk with the help of chemical processes and instruments, could psychological trauma be treated in the same way?

The exhibition Risø resurrects Risø, this time as a research centre for trauma therapy. The instruments and protective gear used here have been developed with the aim of purging psychological trauma. An attempt is made to expel these invisible entities through physical experiments and mental games in the same precarious balancing act between contamination and nutrient loss as applied to milk.

The objective at Risø was to develop nuclear energy in Denmark, but public opposition mounted throughout the 1970s, and in 1985 the plan was abandoned. The facility continued as a research centre, and the dependable reactors attracted scientists from across the globe. In 2000, the biggest reactor was shut down after a suspected leak, and it was decided to decommission the facility. Risø was converted into an interim repository for radioactive waste, which will serve until 2073, by which time a final repository must be found.

Like at the original nuclear research facility, it is not only clean energy that is generated at this research centre for trauma treatment – there is also an accumulation of contaminated material that is passed on as a task for current and future generations to handle.

Instruction / for use. The object is hollow and its upthrust force can carry and keep a human being fixed under water. The frame is attached to the neck and the object, floating in water, will carry the human being below, dead or alive. Porcelain, stainless steel, lacquer Ø38 cm.

Gift, plaster, heroin 130 · 70 · 70 cm.

The Danish word gift means poison; the English word gift means present

Ion exchange, acrylic, porcelain, steel, stainless steel filter, wheel, ion exchange mass 62 · 62 · 212 cm.

Du må ikke forlade mig, steel sheet 160 · 50 · 1 cm.

Escape room, black masonite, steel 280 · 280 · 30 cm.

Photo: GRAYSC